Igor Singer

I am sure all those reading this article will be supportive of Ukrainian citizens blighted by the terrible ongoing conflict in that region. I have been connected with Igor Singer for many years on the social media platform LinkedIn and it is an honour to help to edit this article by Singer, to showcase the rather daring work he is undertaking on war-damaged trees in Ukraine whilst warfare is still ongoing. Due to intermittent electrical supply, it has taken some time to put this article together. All images have been supplied by Singer.

With best wishes, Duncan Slater

This article briefly covers the following issues: restoring landscaping damaged by munitions and de-mining; assessing the damage caused by explosions and their associated craters; estimating the loss of soil coverage and surface plants; and wartime tree risk management.

Restoring landscaping damaged by munitions

It is essential to conduct a visual assessment of the condition of any site before entering and to make an inventory of the most dangerous zones that are degraded or may contain explosives. Taking special care to mark off areas (with signs and ribbons, for example) is critical if there is any suspicion that dangerous material is present, such as unexploded munitions. I have been carrying out research on sapper work and the deactivation of mines and unexploded ordnance. It is important to take these materials ‘out of the field’ if normal landscape and tree work is to be continued. To achieve this, I have been conducting repeated studies on the effects of these munitions (e.g., controls for residues of munitions in plants and trees) to gain an understanding of how planted landscapes can be remediated.

Figure 1: Burnt-out Russian tank and evidence of leaked fluids (gasoline, but also toxic remnants of ammunition, brake fluid and hydraulic fluids) that can contaminate a landscaped area.

Figure 2: Crater caused by the explosion of a Russian missile adjacent to an urban tree, Ukraine, 2022.

Figure 3: Large bomb crater next to several urban trees. Note the extent of thrown-up soil, damage to many roots, and the contaminated pool at the base of the crater.

Assessing damage caused by explosions and craters

Another important aspect of the work is the evaluation of craters caused by explosions (Figs 2 and 3) – the ejection of large amounts of soil and rock as a result of rocket fire, bombing or shelling. In many cases there are some benefits to creating temporary coverings using geo-plastics to lessen the risk of water and wind erosion in a landscaped area. I have also been involved in the creation of temporary ‘drain-traps’, which are labyrinthine channels to slow down the flow of water from slopes and other temporary structures that can help to prevent surface erosion from war-damaged landscaped areas.

Estimating the loss of soil coverage and surface plants

It is important to describe and calculate soil volumes from explosion craters and to mark the backfilling of missing soil. One needs to calculate the likely settlement of the added backfilled soil over time and to carry out compaction of the medium in sequential layers, a method that echoes the medieval practice of building up artificial earth banks and mottes (Hull, 2009).

When a scheme is prepared for reconstructing urban landscape areas, the restoration of fertility in the upper soil profile is desirable. Sowing herbaceous plants, green manure or planting perennials can help with this. Either a manual weeding programme for ruderal herbs and invasives or a herbicide application system (either selective or total) is often needed. It is then a matter of compiling an inventory of the remaining trees and shrubs on the site. When it comes to shrubs, estimating the amount of restoration work that would be required versus replacing the damaged plants entirely is an important consideration. When it comes to larger trees, there are more factors to consider: mature trees are not so easily replaced.

Figure 4: The tracks of a tank have caused extensive damage to the stem of this tree.

Figure 5: Extracting a bullet from the stem of a damaged conifer.

Figure 6: Line of conifers directly damaged by fire at a property in Ukraine.

Figure 7: Indirect fire damage to box plants (Buxus sempervirens) because of their proximity to an intense building fire.

Wartime tree risk management

The current state of the tree must be assessed. First, it is a matter of assessing the damage to the infrastructure around the tree. The danger of adjacent war-damaged buildings falling on it, damage to the tree itself, to its roots, changes to its irrigation and drainage systems can all be caused by the kind of shelling and bombardment that Ukraine has experienced since February 2022. The radius within which there is a significant danger of debris falling is about 1.5 times the height of what survives of a building. Hazardous areas must be marked to alert any other workers who may get involved with landscape restoration or tree management to the dangers.

During my work, I have seen a lot of war damage to urban trees in Ukraine. It is common to see scalped wounds on trunks and branches, fractured trunks, branches and roots, and even the overturning of some trees as a result of an explosion or being driven over by a tank! (Fig. 4)

One of my main tasks is the creation of individual programmes to address wartime tree damage, specifying the order of priorities and determining the cost of the work needed for a tree’s restoration. As part of this process, I use a metal detector to check roots, trunks and branches for the presence of metal fragments and explosive objects. Then I assess the risks associated with the extraction of the objects from the tree concerned (Fig. 5). To help with monitoring, I have created labels for each tree that declare ‘Checked by a metal detector’.

Frequently the structure of a tree has been impacted by munitions and reducing the risk posed by the tree involves some pruning work. Taking the load off unstable parts (e.g., broken branches, cracked trunks) can save many trees, and reduce risks to people too. This work also involves the removal of shattered or damaged tree parts whose restoration is economically and biologically impractical. For dangerous trees where such mitigation is not possible, I ensure that warning signs are placed to advise others of the risks. Sometimes the use of temporary cabling is needed to ensure a tree’s recovery.

It is not worth cleaning tree wounds on parts of a tree that have no chance of regeneration (e.g., a branch that has been excessively crushed or burnt). My restoration work does not consist of one-off tasks since the extent of the living cambium layer is extremely indistinct in such injuries. I must revisit the trees that I treat. After removing metal shrapnel, I create ‘passive wound drainage’ and provide primary treatment against infection (e.g., the use of plant sterilization solutions and/or fungicides). In the case of root damage, I use preventive injections in the damaged areas (e.g., amino acids and fungicides, along with complex water-soluble fertilizers).

I plan to manage the trees in future years, including the regulation of any epicormic growth and to direct the formation of new crowns on severely damaged trees.

Mapping war-damaged trees The presence of tree injuries is often associated with the violation of the mechanical integrity of the tree’s structure. Such injuries include:

- cracks in trunks and branches;

- scalped wounds;

- multiple penetrating wounds into the xylem;

- crushing and laceration wounds (including to the roots);

- burnt areas on the stem and main branches; and

- the chemical impact of liquids (e.g., gasoline, diesel, subcomponents of ammunition).

These injuries need to be recorded on a map so that I can assess their significance to the tree’s vitality and its structure.

Determining the extent of the damage An assessment must be made of the state of the tree’s root system and its surrounding soil (which is critical for the survival of the whole plant). I try to observe whether there has been penetration of toxic substances into the zone where the roots are active. If this is the case then the treatment often involves soil replacement, the addition of drainage, and/or the application of anti-stress drugs (to the tree, of course!).

Unfortunately, the mechanical stability of the tree can be compromised due to violation of the anchoring properties of the root system. In some cases, it is still possible to save such a tree, with the use of temporary cabling and guying, and through the rehabilitation of its roots via treatment of their injuries.

Clarification of the degree of damage to the phloem around the circumference (or ‘girth’) of a tree component (trunk, branch or root) is useful in determining whether that component part can be restored. If the extent of damage is more than 80% of the tree component’s girth, then the work required is either a severe reduction or tree removal because the costs of managing such severely compromised trees are otherwise uneconomic and the work is unlikely to be successful.

Analysis of the damage to a tree is essential, and one needs to consider the possibility of further splitting or crack extension occurring in standing trees. Solutions often lie in either crown reductions to take loading from the tree’s damaged structure, or cabling/bracing.

Figure 8: Shrapnel wounds to the stem of a maple – both glancing and penetrative blows, the latter causing metal fragments to lie within the tree’s tissues.

Figure 9: A projectile (probably a heavy machine-gun bullet) has passed through the stem of this pine tree, leaving an entrance and exit wound.

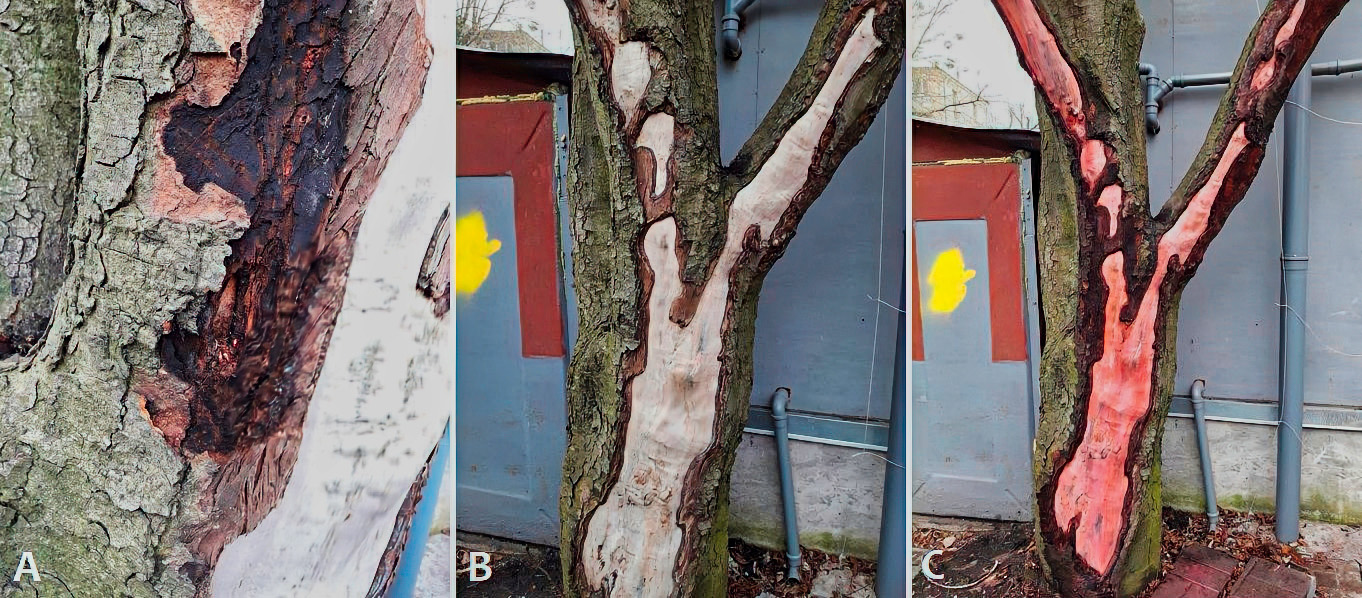

Figure 10: Fire damage to the stem of a mature tree – before (A), during (B) and after treatment (C).

Fire damage assessment Fire damage to war-damaged trees is probably the most difficult to assess since it is difficult to distinguish between living and dead tissues, which can tell you where the formation of woundwood is likely to occur as a rim at the outer edge of the damage through further secondary growth of the tree. In some cases, I track the damage by the removal of the burnt parts of the bark and phloem to their peripheries (Fig. 9), although this is not always possible. It is good practice to remove the severely damaged bark and phloem because if it remains, the growth of the woundwood can be inhibited due to reduced gaseous exchange through the burnt outer covering.

Compression and laceration wounds to trees It is also necessary to estimate the damaged area for compression and laceration wounds, including assessing photosynthetic transport blockage using a calculation method (i.e., an 80/20 rule). Again, wound treatment involves cleansing, potentially sanitation of tissues, and providing passive drainage.

Multiple and penetrating wounds caused by military objects First, I do a check with my metal detector! Assessing the potential for explosive hazards is essential to minimise the risk of injury during this work. I mark the locations of metal objects and determine their nature (e.g., bullet, shell fragment or another projectile) (Figs 8 and 9). A label is added to the tree listing what was found with the metal detector. Then I undertake wound care management around the damage points.

Management of a war-wounded tree Part of the management of war-wounded trees is their protection from diseases (primarily from secondary infections of the wounds I have described above), work on the prevention of stem pests (the second phase of work on these weakened trees) and the introduction of anti-stress drugs, adaptogens and anti-transpirants (the third phase of work). Figure 10 shows some of my remedial work on the stem of a fire-damaged tree. This involved cutting away dead inner bark and burnt tissues to find the rim of woundwood that was developing, and treatment of the stem to prevent secondary infections.

Reference

Hull, L. (2009). Understanding the Castle Ruins of England and Wales. London: McFarland & Company.

Igor Singer is a plantsman and research biologist in his native Ukraine. (Image from Singer’s profile on LinkedIn)

This article was taken from Issue 200 Spring 2023 of the ARB Magazine, which is available to view free to members by simply logging in to the website and viewing your profile area.